Private cars are unsuited to a dense city structure yet they are still widely used. Public transport systems are obviously inadequate.

Even wealthy cities are telling residents that inferior transport is a necessary compromise. They would change habits faster if they developed better services.

Future public transport should be:

1. Nearby

2. Timely

3. Direct

4. Fast

5. Comfortable

6. Safe

7. Cheap

These seven criteria are less obvious than they seem, because few modes of public city transport today can meet more than four of them. Future modes should tick all seven boxes because the motor car can manage five or six.

Unless cities rise to this challenge, the impending era of self-driving cars will begin with worsening road congestion as it increases the advantages of the automobile.

1. Nearby

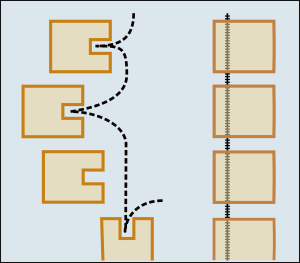

The greatest advantage of the automobile is door-to-door journeys. Before you can board a bus and train you first have to travel to a collection point.

If the bus or train is large and fast, these points or stations will be far apart, so you will need other vehicles for the start and end of your journey. Having to change is an inconvenience for everyone and a major obstacle to the infirm and people with children or luggage.

If the bus or train is large and fast, these points or stations will be far apart, so you will need other vehicles for the start and end of your journey. Having to change is an inconvenience for everyone and a major obstacle to the infirm and people with children or luggage.

The minimum requirement is that the first vehicle’s collection point is nearby, ideally your front door. In regions with an extreme climate, it should enter your building.

It is hard to see how rail vehicles could provide proximity, unless the city is linear and the track passes through each building block.

2. Timely = on demand

In mass transport, schedules are universal. In cities where smart phones are ubiquitous, they are also unnecessary. The vehicle should come when it is summoned, not when it is convenient for the operator to send it. Timetables are also wasteful if they deploy vehicles when no one needs them.

In return for travel on demand, travellers must be ready to give up standard fares. Vehicles summoned at the last moment and during peak hours are more expensive, because the operator will have less capacity available and cannot combine rides efficiently.

A mobile phone app can easily display different travel options, allowing flexible travellers to save money.

3. (Fairly) direct

The ideal journey is one that goes straight from the starting point to the final destination. Mass transport will always require some compromises, but very circuitous journeys are a sign that vehicles are too large in proportion to population density.

In the past, overlarge buses have been a natural response to the high costs and low availability of drivers. This mismatch will end as autonomous road vehicles enter service.

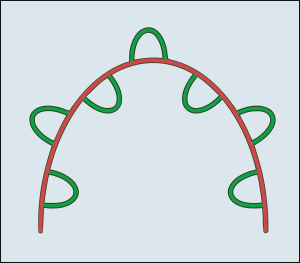

Unfortunately the faith of city planners in rail transport will work in the opposite direction. Light rail systems require thin traffic flows to be merged into thick ones, taking passengers on median routes that meander far from direct ones.

Large vehicles also create a ripple effect when they discharge their passengers, requiring more infrastructure investments to handle congestion.

4. Fast, by total travel time

The best way to save time is by offering the three preceding features – local collection, service on demand and direct journeys. Fast is emphatically not the same as high speed.

The best way to save time is by offering the three preceding features – local collection, service on demand and direct journeys. Fast is emphatically not the same as high speed.

The faster the top speed desired, the greater the distance between stops. Fewer stops and stations spell wasted time as users are required to travel farther before they can begin the high-speed leg of their journey.

Very high speed vehicles are very expensive to build and to operate. Their cost is very often far more than users would voluntarily pay. This explains the correlation between high-speed infrastructure and high transport subsidies from general tax revenues.

5. Comfortable

Concepts of what is comfortable vary greatly, but few would disagree that modern mass transport is generally uncomfortable. Surveys have found that many people think commuting is the least pleasant part of their working day.

Transfers between vehicles and transport modes are usually chaotic, even when timetables have been coordinated to reduce waiting time. And tightly packed trains and buses are always unpleasant and serve to spread common diseases.

Smaller vehicle size can create a great improvement in comfort, on board and also when passengers are discharged.

6. Safe

The inclusion of this criterion is almost pro forma. In developed countries there is no significant danger in travelling by train, metro (light rail), or bus (coach). However, travel by car is more likely to result in death.[1]

Although accident rates will fall as automated driving systems become widespread and then compulsory,[2] this is the one box that private cars don’t tick.

7. Cheap

Low-cost projects should obviously be preferred to expensive projects that achieve no more. But in city politics, high cost is sometimes not only acceptable but even admirable.

This happens when city leaders argue that the preferred project will serve greater goals that are harder to quantify or predict, like reducing road congestion, promoting employment, boosting housebuilding, or saving the planet.

Take Helsinki’s runaway train, an orbital light railway called the “Raidejokeri”. Prices of prestige projects often experience inflation in their later stages; costs are initially underestimated to get the project started, after which it becomes practically unstoppable. But the Raidejokeri doubled in price to about €460 million before construction even began.

The city could make large savings by building a new orbital road instead. If the orbital was reserved for public transport (and emergency vehicles), it would allow all bus services to go far faster.

Unlike monstrous trams on rails, these buses would be able to leave the orbital to pick up and set down passengers outside their homes and offices. This in turn would allow the orbital route to be straightened, instead of having to snake around the suburbs.

So the orbital road for public buses would be shorter. It would reduce total journey times. And it would save the city at least €200 million.

But the light railway is what is being built. There is already a website extolling its virtues, most of them rather fanciful.

Conclusion

The way to reduce the use of cars is not to appeal to the altruism of passengers but to offer alternative transport that meets their needs.

Instead of great size, weight and speed, an advanced city should offer agile transport on demand.

The key to making mass transport more usable and efficient is to reduce mass.

Postscript

Rails vs. roads

There is a modern fascination for trains and even trams.[3] They hum as they accelerate; their doors open and close with a satisfying swish.

This was the cartoon future we saw on TV when we were kids. By ordering yesterday’s vision of the future, city leaders obtain international bragging rights among colleagues with the same childish memories.

But vehicles that run on rails can’t collect passengers from their homes. They can’t provide service on demand. They don’t offer the most direct route from A to B. And they can’t be rerouted in special circumstances.

Trams and trains are far more expensive than modern buses and are less fuel-efficient.[4] Even more greenhouse gases are produced when their tracks and stations are constructed. Manufacturers in this sector have not kept up with the automotive industry in technological development.

When the next generation of electrically powered, driverless road vehicles becomes available in the 2020s, rail vehicles will fall even farther behind.

Endnotes

[1] Savage, I. (2013). Comparing the fatality risks in United States transportation across modes and over time. Research in Transportation Economics 43, 9-22.

[2] Humphreys, P. (2016). Mobility 2020. Transport & Travel.

[3] Withrington, P. (2011). Rail versus road. Institute of Economic Affairs.

[4] Lawyer, David S. (2007). Fuel efficiency of travel in the 20th Century. L.A. FreeNet.